Recently, the New York Times published a front page story headlined “Murder Rates Rising Sharply in Many U.S. Cities.” Much of the media have run similar reports, including USA Today, Reuters and Time.

First we must consider whether the storyline is entirely true. Both the Washington Post’s Wonkblog and FiveThirtyEight wrote analyses demonstrating that there is no uniform rise in violent crime across all or even most cities. According to data compiled by FiveThirtyEight, comparing similar periods in 2014 to 2015, homicides decreased or stayed the same in 23 of America’s 60 biggest cities.

Across all 60 of these cities, however, the number of homicides from January through mid-August increased from 2,963 in 2014 to 3,450 in 2015, a rise of 16 percent. And there have been undeniably significant increases in murder in Baltimore, Chicago, Houston, Louisville, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Omaha, St. Louis, Tulsa and the District of Columbia.

It seems something awful is happening. Yet, we must cautiously qualify that statement. Since the late 1980s, murder, violent crime, and crime in general have all plummeted. The United States has become tremendously safer over the past 30 years—although no one really seems to know why.

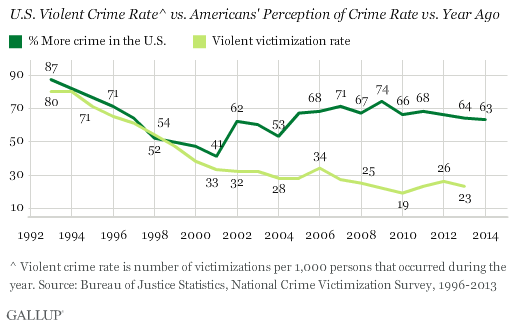

And we don’t want to alarm the public; they’re overly alarmed already. As the Gallup poll regularly demonstrates, for the past few decades, Americans have always believed that crime was increasing while it was actually falling—indeed, falling dramatically.

That said, is there a logical reason why homicide has increased significantly in cities like Baltimore and Washington, D.C. while other places like Philadelphia and New York have seen little change?

Advocates, law enforcement officials and mayors have offered up a variety of explanations. Some say it’s because there are so many guns on the streets, and that is true, but the supply has not changed in recent years. Some say the shootings are largely the work of offenders who have previously been in the criminal justice system, which is also true, but again there’s nothing new or different about it.

One particularly scurrilous claim is the idea of a “Ferguson effect,” that less aggressive policing has emboldened criminals. This is so lacking in evidence and so clearly based on emotion and ideology that it shouldn’t have to be dignified by a rebuttal. But just for the record, in nearly all of the cities that have seen a lot more homicides, there’s been no less aggressive policing.

Logic suggests that the cause has to be some factor that exists across the nation but might affect different cities differently. Could it be the recent precipitous increase in the use of synthetic drugs? Some of these substances, which are cheap and widely available in high-poverty neighborhoods, are believed to cause at least some users to become irrationally violent.

In Washington, D.C., it appears that people are rapidly escalating garden-variety disputes, as if they were out of their minds. Things that used to culminate in insults or fists thrown are now ending in gunfire. There is a reasonable amount of anecdotal evidence that synthetic drugs are a factor in the rise of violence in our Nation’s Capital.

If synthetic drugs are linked to violence, that could explain why some cities have a problem and others don’t. The active ingredients in these synthetic drugs, and their “normal” doses, are all different; the violence-inducing products could be especially prevalent in certain cities.

What is to be done? The most sensible course of action is study. Are synthetic drugs an important factor in recent violence, and if so, are there any workable policy solutions? Usually drug policy focuses, unsuccessfully, on blocking supply or punishing users. What about focusing on demand?

For example, one of the reasons people take synthetic drugs is they don’t show up in drug tests. If individuals are tested for drug use because they are in the parole or probation system, or their jobs mandate it, or the tests are required to receive social services, synthetic drugs may be seen as having an advantage over marijuana (which can be detected for many days or weeks). Are government-mandated tests for marijuana use doing anything other than driving up sales of much more dangerous synthetic drugs?