Last week’s column explained the science behind political stubbornness. Essentially, our brains are hard-wired to engage in “confirmation bias.” Further, our opponents get a blast of dopamine and feel pleasure after they rebut our arguments—even when that rebuttal is based on irrationality and falsehood. By the end of last week’s column it may have seemed like political persuasion is virtually impossible.

And yes, it is extremely difficult to change the minds of partisans. There are conservatives, for example, who are unpersuadable no matter how many scientists testify to the truth of global warming, no matter how much evidence shows that the death penalty doesn’t deter murder, no matter the incontestability that voter fraud at the polls is too rare to worry about.

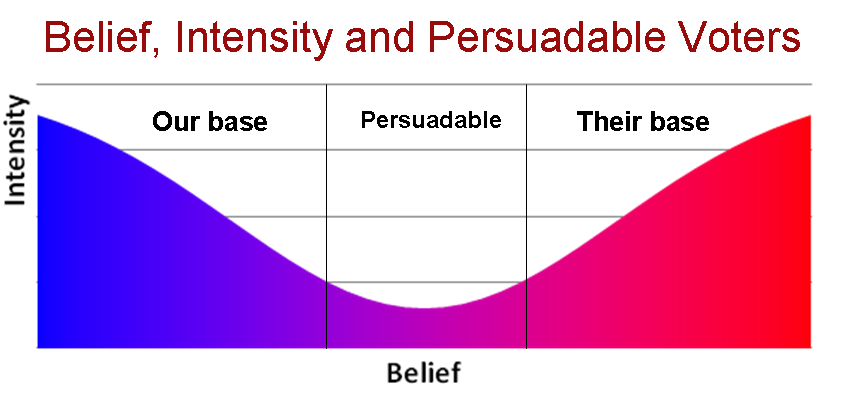

In fact, politics isn’t really about changing our opponents’ minds. It’s about mobilizing our own base while persuading that slice of voters who are persuadable.

Inside the minds of average voters

The brains of swing voters work the same as ours, of course. What makes them persuadable is that they’re not trying so hard to “confirm” their right- or left-wing preconceptions. Persuadable voters don’t lack political beliefs, biases and stereotypes. Instead, they carry in their minds both progressive and conservative ideas—and they can be persuaded by either. At the same time, they don’t tend to hold onto those beliefs with the intensity of partisans, so they don’t feel as much emotional need to defend them.

To persuade these Americans, we must appeal to beliefs already in their brains that support our solutions and steer away from preconceptions that seem to justify conservative policies. In addition, we need to avoid negative emotional triggers (explained in Part One) so a listener will engage his or her rational cerebral cortex. This is essential: Don’t trigger a negative emotional response. Be aware that in a listener’s head there’s an emotional traffic light; don’t turn it red, stopping him or her from following your argument—or even listening to it.

Here are five rules to overcome confirmation bias and emotional triggers.

#1 Never say “you’re wrong.”

Quite simply, if you say “you’re wrong” your listener will stop listening. You need to engage the part of his or her brain that will reflect on your argument, not react to it. Similarly, never let your own emotions do the talking. When you are about to speak in anger, take a deep breath and shake it off. Voicing your emotions will make you feel good—you’ll get a shot of dopamine in your brain—but it won’t help you persuade.

#2 Use praise, friendliness and body language to trigger positive feelings.

Praise something about your listener(s), smile, project friendliness and confidence. Indicate that you are in some way part of the same group, or you’re on the same side. It’s not that people will adopt your political positions because they like you; it’s that they will keep their minds open. Or as psychology professor Peter Ditto explains: “When people have their self-worth validated in some way, they tend to be more receptive to information that challenges their beliefs.”

#3 Begin any argument in agreement with your listener(s).

Find a point of agreement; give your audience a bridge from their preconceptions to your solutions. The goal is not to change people’s minds, it is to show them that they agree with you already. Begin by expressing empathy and shared values. Demonstrate that you understand their problems and concerns. Voters quite reasonably conclude that you can’t fix their problems if you can’t understand them. Read much more about starting in agreement in our book Voicing Our Values: a message guide for candidates and lawmakers.

#4 Don’t use emotionally charged phrases.

Progressives often talk to persuadable voters the way we talk to friends in our base. We might say “corporate greed,” or “military industrial complex,” or words that end in “ism.” We think we’re speaking plainly but persuadables really don’t understand what we mean, and such language will alienate them. Or we might draw sharp conclusions about our opponents’ proposals, saying they’re “immoral” or “insane.” These characterizations may be accurate, nevertheless persuadable voters will stop listening. This kind of language makes progressives feel better; it pushes our happy buttons. But for the uncommitted listener, it’s a red light.

#5 Avoid factual arguments that voters flatly disbelieve.

This is a hard one for most progressives. Unfortunately, sometimes a truthful statement can be a negative trigger. Listeners will instantly engage their emotions instead of their intellects and you’ve utterly failed to persuade. For example, you just can’t move voters to our side by saying that widespread voter fraud is a myth, even though it is. Use other language (here) to argue against voter ID. If you need to walk your listener away from false information, your best shot is to ask them to explain why they hold a particular opinion. Sometimes “[t]hey will come to realize the limitations of their own understanding” notes psychologist Frank Keil.

We often have reason to view our opponents as “irrational.” They are arguing against their own best interests and using phony information as proof. But understand, they are simply engaged in runaway confirmation bias. They truly believe what they believe. People who disagree with us aren’t crazy, they are human. Some can be persuaded and others can’t. To be successful in politics, we need to accept this and make the best of it.